Нам хотелось, чтобы наши карьеры действительно меняли мир к лучшему, поэтому мы стали искать, в каких областях наши усилия будут наиболее эффективными и приведут к максимальному позитивному сдвигу.

Наш анализ показал, что выбор правильной задачи для применения своих навыков может увеличить ваш вклад более чем в 100 раз, и это может стать самым важным решением в вашей жизни.

Пытаясь ответить на данный вопрос, нам пришлось подвергнуть сомнению всё, о чём мы думали, что знаем, а затем делать это снова и снова.

Здесь приведен конспект того, что мы узнали.1 Прочтите, чтобы узнать, почему прекращение диареи может спасти столько же жизней, сколько прекращение войны во всём мире, почему искусственный интеллект может быть даже важнее всего этого, и что делать со своей карьерой, чтобы решить самые неотложные проблемы мира.

Если кратко, то самые насущные задачи - это те, решая которые, люди окажут наибольшее влияние на будущее. Как мы объясняли в предыдущей статье, это означает что решаемые задачи являются не только большими, но также пренебрегаемыми и решаемыми. Чем более они пренебрегаемы и решаемы, тем больше окажется вклад человека, который возьмётся их решать. Получается, что это совсем не те проблемы, которые первыми приходят на ум.

Время чтения: 30 минут. Если вы просто хотите увидеть наш текущий список самых насущных мировых задач, то можно сразу перейти к нужной статье.

Почему проблемы богатых стран зачастую не самые важные-и почему благотворительность не всегда должна начинаться дома

Большинство людей, которые хотят творить добро, фокусируются на проблемах своей страны. В богатых странах это означает решение проблем бездомных, безработицы, стремления дать образование бедным слоям населения. Но это ли самые срочные задачи?

В США, только 4% взносов на благотворительность тратятся на международные нужды.2 Наиболее популярными карьерами для талантливых выпускников, которые хотят творить добро, являются сферы обучения и здравоохранения, в которые приходят примерно 18% выпускников, при этом в основном помощь получают граждане США.3

Есть веские причины, чтобы сосредоточиться на помощи в своей собственной стране - вы знаете больше о ее проблемах и можете чувствовать особые обязательства перед ней. Однако еще в 2009 году мы столкнулись с фактами, которые заставили нас думать, что наиболее насущные проблемы не локальные, а глобальные, касающиеся беднейших стран мира, особенно в сфере здравоохранения, такие как борьба с малярией и паразитическими червями.

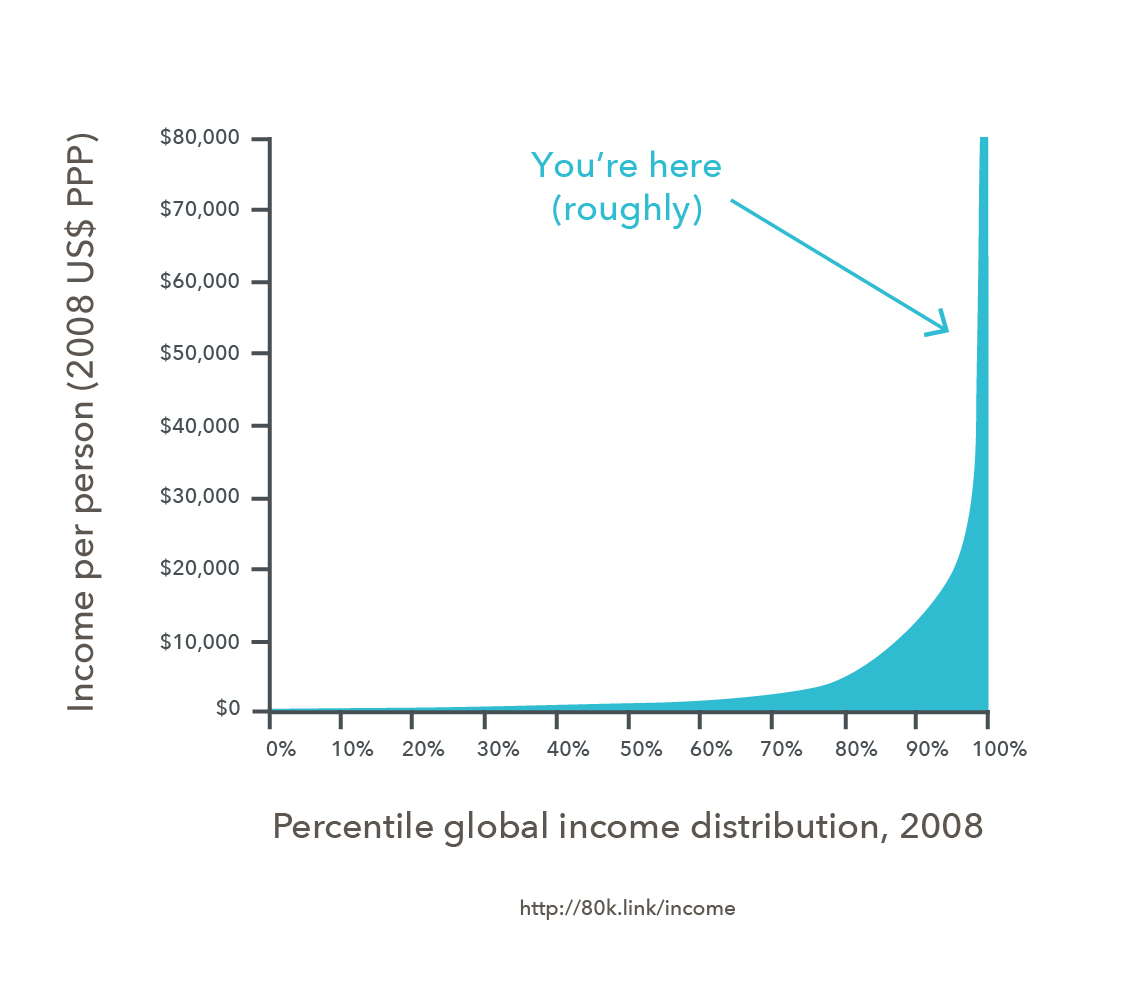

Почему мы так говорим? Вот довольно впечатляющий график, с которым мы столкнулись в нашем исследовании.

Это распределение мирового дохода, которое мы видели в предыдущей статье.

Даже тот, кто живет в США за чертой бедности в 11 000 долларов в год богаче, чем примерно 85% населения мира, и примерно в 20 раз богаче, чем самые бедные в мире 1,2 миллиарда человек, которые в основном живут в Африке и Азии на сумму менее 500 долларов в год. Эти цифры уже скорректированы с учетом того, что в бедных странах деньги идут дальше (по паритету покупательной способности).5

As we also saw earlier, the poorer you are, the bigger difference extra money makes to your welfare. Based on this research, because the poor in Africa are 20 times poorer, we’d expect resources to go about 20 times further in helping them.

There are also only about 47 million people living in relative poverty in the US, about 6% as many as the 800 million in extreme global poverty.6

And there are far more resources dedicated to helping this smaller number of people. Total overseas development aid is only about $131bn per year, compared to $900bn spent on welfare in the US.7

Finally, as we saw earlier, the majority of US social interventions probably don’t work. This is because problems facing the poor in rich countries are complex and hard to solve. Moreover, even the most evidence-backed interventions are expensive and have modest effects.

The same comparison holds for other rich countries, such as the UK, Australia, Canada and the EU. (Though if you live in a developing country, then it may well be best to focus on issues there.)

All this isn’t to deny the poor in rich countries have very tough lives, perhaps even worse in some respects than those in the developing world. Rather, the issue is that there are far fewer of them, and they’re harder to help.

So if you’re not focusing on issues in your home country, what should you focus on?

Global health: a problem where you could really make progress.

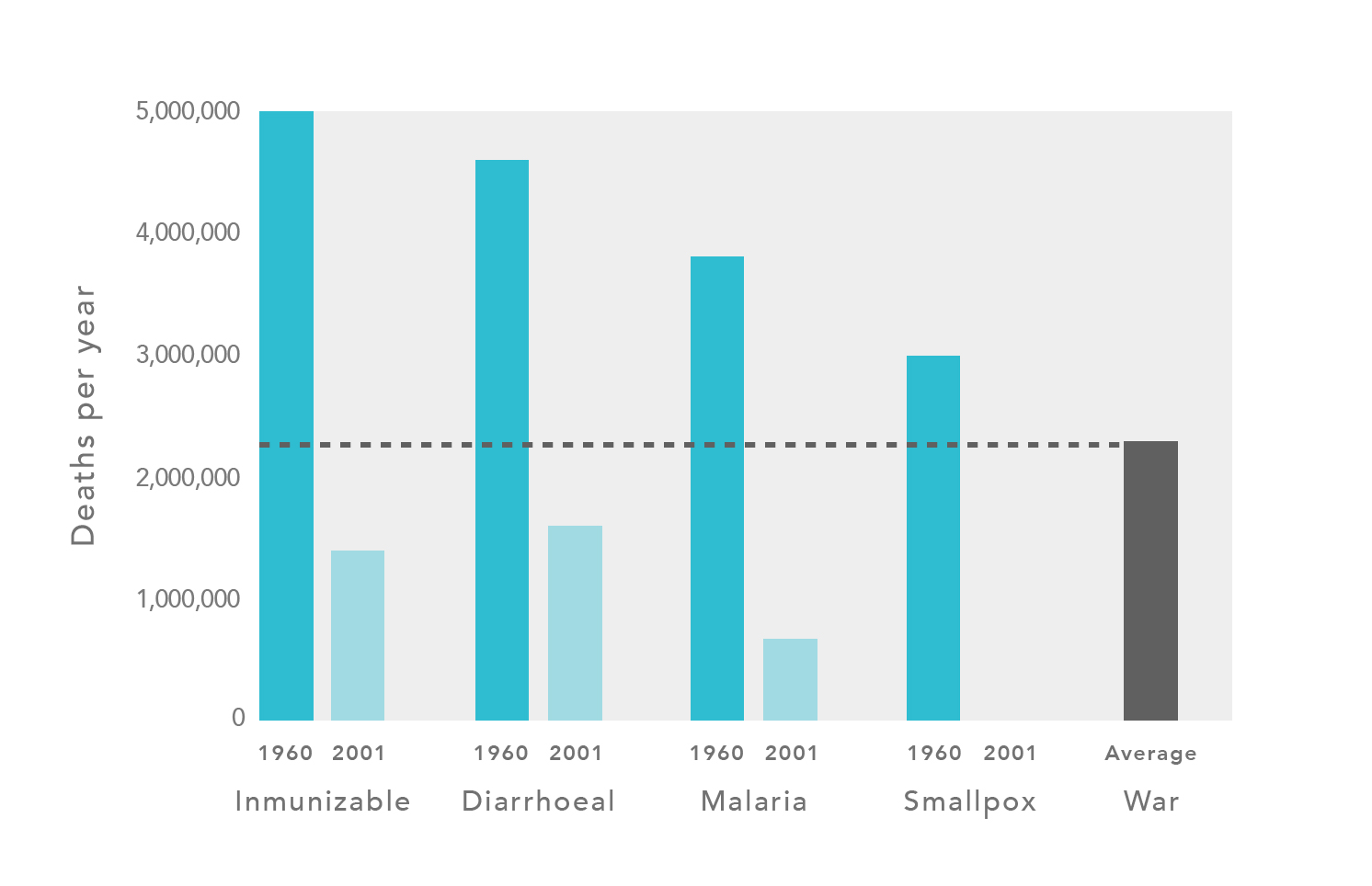

What if we were to tell you that, over the second half of the 20th century, progress on treatments for diarrhoea did as much to save lives as achieving world peace over the same period would have done?

The number of deaths each year due to diarrhoea have fallen by 3 million over the last four decades due to advances like oral rehydration therapy.

Meanwhile, all wars and political famines killed about 2 million people per year over the second half of the 20th century.8

The global fight against disease is one of humanity’s greatest achievements, but it’s also an ongoing battle to which you can contribute with your career.

For instance, William Easterly, author of White Man’s Burden, wrote:

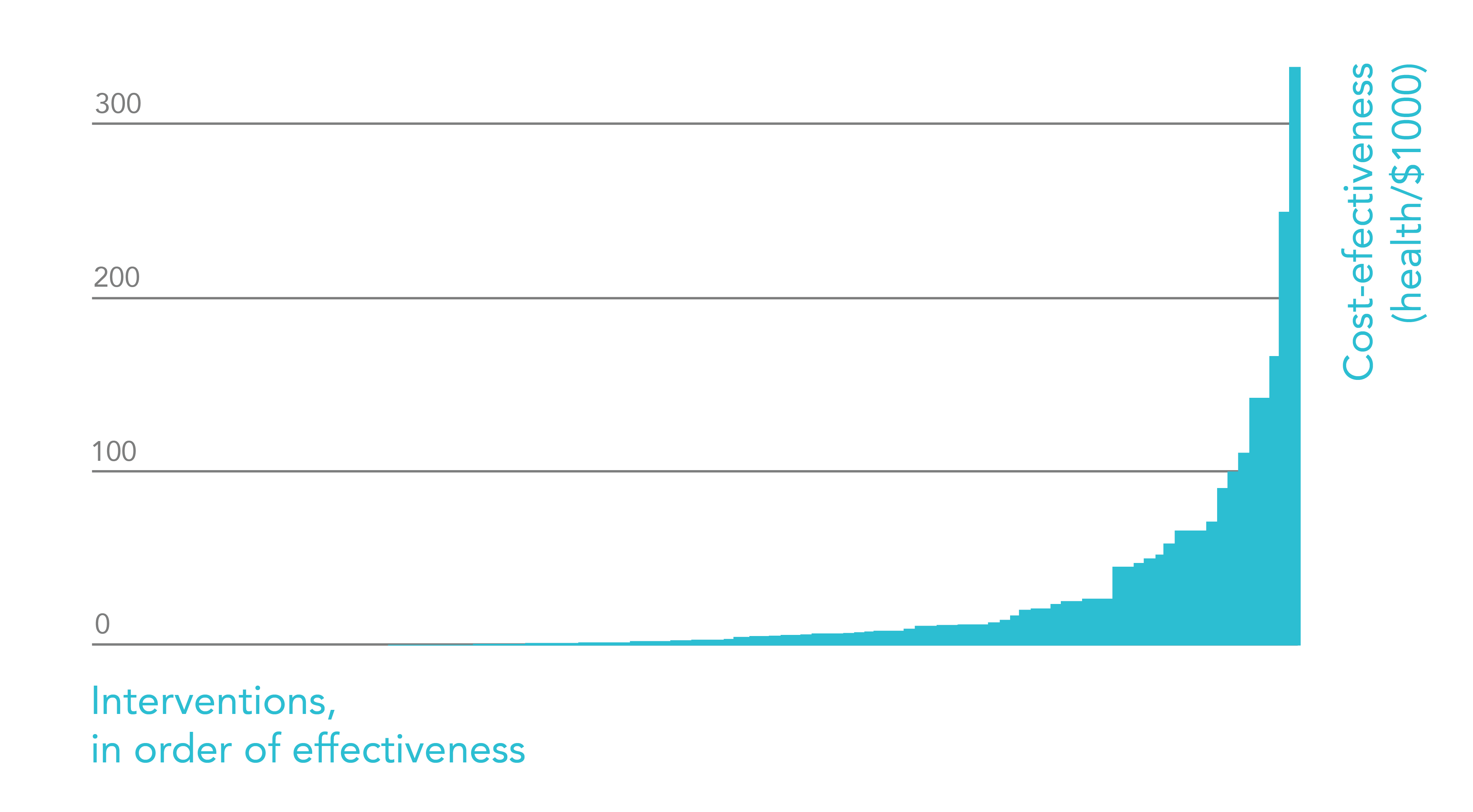

Put the focus back where it belongs: get the poorest people in the world such obvious goods as the vaccines, the antibiotics, the food supplements, the improved seeds, the fertilizer, the roads…. This is not making the poor dependent on handouts; it is giving the poorest people the health, nutrition, education, and other inputs that raise the payoff to their own efforts to better their lives.Within health, where to focus? An economist at the World Bank sent us this data, which also amazed us.

The first point is that all these treatments are effective. Essentially all of them would be funded in countries like the US and UK. People in poor countries, however, routinely die from diseases that would certainly have been treated if they’d happened to have been born somewhere else.

Even more surprising, however, is that the top interventions are far better than the average, as shown by the spike on the right. The top interventions, like vaccines, have been shown to have significant benefits, but are also extremely cheap. The top intervention is over ten times more cost-effective than the average, and 15,000 times more than the worst.9 This means if you were working at a health charity focused on one of the top interventions, you’d expect to have ten times as much impact compared to a randomly selected one.

This study isn’t perfect – there were mistakes in the analysis affecting the top results (and that’s what you’d expect due to regression to the mean) – but the main point is solid: the best health interventions are many times more effective than the average.

So how much more impact might you make with your career by switching your focus to global health?

Because, as we saw in the first chart, the world’s poorest people are over 20 times poorer than the poor in rich countries, resources go about 20 times as far in helping them (read about why here).

Then, if we focus on health, there are cheap, effective interventions that everyone agrees are worth doing. We can use the research in the second chart to pick the very best interventions, letting us have perhaps five times as much impact again. In total, this makes for a 100-fold difference in impact.

Does this check out? After years of research, analysts at GiveWell have estimated that spending $7,500 on 1,500 malaria nets through the Against Malaria Foundation is enough, on average, to prevent one death.10

In contrast, in rich countries like the US, it usually costs over $1m to save another life with health spending.11 So if we compare health in the US to global health, there is a 130-fold difference.12

It’s hard for us to grasp such big differences in scale, but that would mean that one year of (equally skilled) effort towards the best treatments within global health could have as much impact as 130 years – three career’s worth of time – working on typical rich country issues.

These discoveries caused us to start giving at least 10% of our income to effective global health charities. No matter which job we ended up in, these donations would enable us to make a significant difference. In fact, if the 100-fold figure is correct, a 10% donation would be equivalent to donating 1,000% of our income to charities focused on poverty in rich countries.

See more detail on how to contribute to global health in our full profile.

We considered lots of avenues to help the global poor, like trade reform or promoting migration, or crop yield research, or biomedical research.

We also seriously considered working to end factory farming. For example, we helped to found Animal Charity Evaluators, which does research into how to most effectively improve animal welfare. We still think factory farming is an urgent problem, as we explain in our full profile. But in the end, we went in a different direction.

Why focusing on future generations can be even more effective than tackling global health

Which would you choose from these two options?

- Prevent one person from suffering next year.

- Prevent 100 people from suffering (the same amount) 100 years from now.

If people didn’t want to leave a legacy to future generations, it would be hard to understand why we invest so much in science, create art, and preserve the wilderness.

We would certainly choose the second option. And if you value future generations, then there are powerful arguments that you should focus on helping them. We were first exposed to these by researchers at the University of Oxford’s (modestly named) Future of Humanity Institute, with whom we affiliated in 2012.

So, what’s the reasoning?

First, future generations matter, but they can’t vote, they can’t buy things, and they can’t stand up for their interests. This means our system neglects them. You can see this in the global failure to come to an international agreement to tackle climate change that actually works.

Second, their plight is abstract. We’re reminded of issues like global poverty and factory farming far more often. But we can’t so easily visualise suffering that will happen in the future. Future generations rely on our goodwill, and even that is hard to muster.

Third, there will probably be many more people alive in the future than there are today. The Earth will remain habitable for at least hundreds of millions of years.13 We may die out long before that point, but if there’s a chance of making it, then many more people will live in the future than are alive today.

If each generation lasts for 100 years, then over 100 million years there could be one million future generations.

This is such a big number that any problem that affects future generations potentially has a far greater scale than one that only affects the present – it could affect one million times more people, and all the art, science and culture that will entail. So problems that affect future generations are potentially the largest in scale and the most neglected.

What’s more, because the future could be long and the universe is so vast, almost no matter what you value, there could be far more of what matters in the future.

This suggests that probably what most matters morally about our actions is their effect on the future. We call this the “long-term value thesis”. We cover it in more depth in a separate article.

This said, can we actually help future generations, or improve the long-term? Perhaps the problems that affect the future are big and neglected, but not solvable?

How to preserve future generations – find the more neglected risks

In the summer of 2013, Barack Obama referred to climate change as “the global threat of our time.” He’s not alone in this opinion. When many people think of the biggest problems facing future generations, climate change is often the first to come to mind.

We think those people are, to some extent, on the right track. The most powerful way we can help future generations is, we think, to prevent a catastrophe that could end advanced civilization, or even prevent any future generations from existing. If civilisation survives, we’ll have a chance to later solve problems like poverty and disease; while climate change poses an existential threat. (We argue for this in greater detail elsewhere.)

However, climate change is also widely acknowledged as a major problem (Donald Trump aside), and receives tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars of investment. You can read more in our full profile.

So, if you want to help future generations, we think it’s likely higher-impact to focus on more neglected issues.

Biorisk: The threat from future disease

In 2006, The Guardian ordered segments of smallpox DNA via mail. If assembled into a complete strand and transmitted to 10 people, public health experts estimate it would have killed 10 million people.14

The chance of a pandemic that kills over 100 million people over the next century seems similar to the risk of nuclear war or runaway climate change. So it poses a similar threat both to the present generation and future generations.

But risks from pandemics are more neglected. We estimate that about $300bn is spent annually on efforts to fight climate change, compared to $1-$10bn towards biosecurity – efforts to reduce the risk of natural and man-made pandemics.

At the same time, there’s plenty that could be done to improve biosecurity, such as improving regulation of labs and developing cheap diagnostics to detect new diseases quickly. Overall, we think biosecurity is likely more urgent than climate change.

Read more about how to contribute to biosecurity in our full profile.

Similar arguments could also be made for nuclear security, though it’s a bit less neglected and harder for individuals to work within.

But there are issues that might be even more important, and even more neglected.

Artificial intelligence and the ‘alignment problem’

Around 1800, civilisation underwent one of the most profound shifts in human history: the industrial revolution.15

One candidate is bioengineering – the ability to fundamentally redesign human beings – as covered by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens.

But we think there’s an even bigger issue that’s even more neglected: artificial intelligence.

Billions of dollars are spent trying to make artificial intelligence more powerful, but hardly any effort is devoted to making sure that those added capabilities are implemented safely and for the benefit of humanity.

This matters for two main reasons.

First, powerful AI systems have the potential to be misused. For instance, if the Soviet Union had developed nuclear weapons far in advance of the USA, then it might have been able to use them to establish itself as the leading global super power. Similarly, the development of AI might also destablise the global order, or lead to a concentration of power, by giving one nation far more power than it currently has.

Second, there is a risk of accidents when powerful new AI systems are deployed. This is especially pressing due to the “alignment problem.”

This is a complex topic, so if you want to explore it properly, we recommend reading this article by Wait But Why, or watching the video below.

In the 1980s, chess was held up as an example of something a machine could never do. But in 1997, world chess champion Garry Kasparov was defeated by the computer program Deep Blue. Since then, computers have become far better at chess than humans.

In 2004, two experts in artificial intelligence used truck driving as an example of a job that would be really hard to automate. But today, self-driving cars are already on the road.16

In 2014, Professor Bostrom predicted that it would take ten years for a computer to beat the top human player at the ancient Chinese game of Go. But it was achieved in March 2016 by Google DeepMind.17

The most recent of these advances are possible due to progress in a type of AI technique called “machine learning”. In the past, we mostly had to give computers detailed instructions for every task. Today, we have programs that teach themselves how to achieve a goal. The same algorithm that can play Space Invaders below has also learned to play about 50 other arcade games. Machine learning has been around for decades, but improved algorithms (especially around “deep learning” techniques), faster processors, bigger data sets, and huge investments by companies like Google have led to amazing advances far faster than expected.

Due to this, many experts think human-level artificial intelligence could easily happen in our lifetimes. Here is a survey of 100 of the most cited AI scientists:18

| Median response | Mean response | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% chance of human-level machine intelligence | 2024 | 2034 | 33 years |

| 50% chance of human-level machine intelligence | 2050 | 2072 | 110 years |

| 90% chance of human-level machine intelligence | 2070 | 2168 | 342 years |

Why is this important? Gorillas are faster than us, stronger than us, and have a more powerful bite. But there are only 100,000 gorillas in the wild, compared to seven billion humans, and their fate is up to us.19 A major reason for this is a difference in intelligence.

Right now, computers are only smarter than us in limited ways (e.g. playing chess), and this is already transforming the economy. The key moment, however, is when computers become smarter than us in most ways, like how we’re smarter than gorillas.

This transition could be hugely positive, or hugely negative. On the one hand, just as the industrial revolution automated manual labour, the AI revolution could automate intellectual labour, unleashing unprecedented economic growth.

But we also couldn’t guarantee staying in control of a system that’s smarter than us – it would be more strategic than us, more persuasive, and better at solving problems. What happens to humanity after its invention would be up to it. So we need to make sure the AI system shares our goals, and we only get one chance to get the transition right.

This, however, is not easy. No-one knows how to code moral behaviour into a computer. Within computer science, this is known as the alignment problem.

Solving the alignment problem might be one of the most important research questions in history, but today it’s mostly ignored.

The number of full-time researchers at or beyond the postdoc level working directly on the control problem is under 30 (as of early 2018), making it some 100 times more neglected than biosecurity.

At the same time, there is momentum behind this work. In the last five years, the field has gained academic and industry support,20 such as a leading author of AI textbooks, Stuart Russell, and Stephen Hawking, as well as major funders, like the groundbreaking entrepreneur and billionaire Elon Musk. If you’re not a good fit for technical research yourself, you can contribute by working as a research manager or assistant, or donating and raising funds for this research.

This will also be a huge issue for governments. AI policy is fast becoming an important area, but policy-makers are focused on short-term issues like how to regulate self-driving cars and job loss, rather than the key long-term issues (i.e. the future of civilisation).

You can find out how to contribute in our full profile.

Of all the issues we’ve covered so far, solving the alignment problem and managing the transition to powerful AI are among the most important, but also by far the most neglected. Despite also being harder to solve, we think they’re likely to be among the most high-impact problems of the next century.

This was a surprise to us, but we think it’s where the arguments lead. These days we spend more time researching machine learning than malaria nets.

Read more about why we think reducing extinction risks should be humanity’s key priority.

Dealing with uncertainty, and “going meta”

Our views have changed a great deal over the last eight years, and they could easily change again. We could commit to working on AI or biosecurity, but we might discover something even better in the coming years. Might there be problems that will definitely be important in the future, despite all our uncertainty?

Eventually, we decided to work on career choice, which is why we’re writing this article. In this section, we’ll explain why, and suggest other problems that are more attractive the more you’re uncertain. We think these are potentially competitive with AI and biosecurity, and where to focus mainly comes down to personal fit.

Global priorities research

If you’re uncertain which global problem is most pressing, here’s one answer: “more research is needed”. Each year governments spent over $500 billion trying to make the world a better place, but only a tiny fraction goes towards research to identify how to spend those resources most effectively – what we call “global priorities research”.

As we’ve seen, some approaches are far more effective than others. So this research is hugely valuable.

A career in this area could mean working at the Open Philanthropy Project, Future of Humanity Institute, economics academia, think tanks, and elsewhere. Read more about how to contribute in the full profile.

Broad interventions, such as improved politics

The second strategy is to work on problems that will help us solve lots of other problems. We call these “broad interventions”.

For instance, if we had a more enlightened government, that would help us solve lots of other problems facing future generations. The US government in particular will play a pivotal role in issues like climate policy, AI policy, biosecurity, and new challenges we don’t even know about yet. So US governance is highly important (if maybe not neglected or tractable).

This consideration brings us full circle. Earlier, we argued that rich country issues like education were less urgent than helping the global poor. However, now we can see that from the perspective of future generations, some rich country issues might be more important, due to their long-term effects.

For instance, a more educated population might lead to better governance; or political action in your local community might have an effect on decision-makers in Washington. We did an analysis of the simplest kind of political action – voting – and found that it could be really valuable.

On the other hand, issues like US education and governance already receive a huge amount of attention, which makes them hard to improve. Read more about the case against working on US education.

We favour more neglected issues with more targeted effects on future generations. For instance, fascinating new research by Philip Tetlock shows that some teams and methods are far better at predicting geopolitical events than others. If the decision-makers in society were informed by much more accurate predictions, it would help them navigate future crises, whatever those turn out to be.

However, the category of “broad interventions” is one of the areas we’re most uncertain about, so we’re keen to see more research.

Capacity building and promoting effective altruism

If you’re uncertain which problems will be most pressing in the future, a third strategy is to simply save money or invest in your career capital, so you’re in a better position to do good when you have more information.

However, rather than make personal investments, we think it’s even better to invest in a community of people working to do good.

Our sister charity, Giving What We Can, is building a community of people who donate 10% of their income to whichever charities are most cost-effective. Every $1 invested in growing GWWC has led to $6 already donated to their top recommended charities, and a total of almost one billion dollars pledged.

By building a community, they’ve been able to raise more money than their founders could have donated individually – they’ve achieved a multiplier on their impact.

But what’s more, the members donate to whichever charities are most effective at the time. If the situation changes, then (at least to some extent) the donations will change too.

This flexibility makes the impact over time much higher.

Giving What We Can is one example of several projects in the effective altruism community, a community of people who aim to identify the best ways to help others and take action.

80,000 Hours itself is another example.

Better career advice doesn’t sound like one of the most pressing problems imaginable. But many of the world’s most talented young people want to do good with their lives, and lack good advice on how to do so. This means that every year, thousands of them have far less impact than they could have.

We could have gone to work on issues like AI ourselves. But instead, by providing better advice, we can help thousands of other people find high-impact careers. And so, we can have thousands of times as much impact ourselves.

What’s more, if we discover new, better career options than the ones we already know about, we can switch to promoting them. Just like Giving What We Can, this flexibility gives us greater impact over time.

We call the indirect strategies we’ve covered—global priorities research, broad interventions, and promoting effective altruism—“going meta”. This is because they work one level removed from the concrete problems that seem most urgent.

The downside of going meta is that it’s harder to know if your efforts are effective. The advantage is they’re usually more neglected, since people prefer concrete opportunities over more abstract ones, and they allow you to have greater impact in the face of uncertainty.

Find out more about promoting effective altruism

How to work out which problems you should focus on

You can see a list of almost all the problems we’ve covered here:

We’ve scored the problems on scale, neglectedness and solvability to help make our reasoning clearer. You can read about how we came up with the scores here. Take the scores with a fist full of salt.

The assessment of problems also greatly depends on value judgements and debatable empirical questions, so we expect people will disagree with our ranking. To help, we made a tool that asks you some key questions, then re-ranks the problems based on your answers.

Finally, factor in personal fit. We don’t think everyone should work on the number one problem. If you’re a great fit for an area, you might have over 10 times as much impact as in one that doesn’t motivate you. So this could easily change your personal ranking.

Just remember there are many ways to help solve each problem, so it’s usually possible to find work you enjoy. Moreover, it’s easier to develop new passions than most people expect.

Despite all the uncertainties, your choice of problem might be the single biggest decision in determining your impact.

If we rated global problems in terms of how pressing they are, we might intuitively expect them to look like this:

But instead, we’ve found that it looks more like this.

If there’s one lesson we draw from all we’ve covered, it’s this: if you want to do good in the world, it’s worth really taking the time to learn about different global problems, and how you might contribute to them. It takes time, and there’s a lot to learn, but it’s hard to imagine anything more interesting, or more important.

Apply this to your own career

Using the resources above, write down the three global problems that you think are most pressing for you to work on. Your personal list will depend on your values, empirical assumptions, and personal fit with the areas.

For each problem, list out some specific career options you could take that would help the problem. You can get ideas in our profiles, as well as further reading on each area. Also remember you can contribute to any problem area through donations and advocacy, even if it’s not the focus of your day job.

This list of problems is just a starting point. The next step is to find concrete career options that will make a difference within the area, which we cover in the next article, then to find an option with excellent personal fit, which we also cover later.

Part 6:Which careers are highest impact?

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide.

No time now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week.