Take for example sponsored skydiving, which has become a popular way to raise money for charity in the UK. Every year, thousands of people collect donations for good causes and then throw themselves out of planes to draw attention to whatever charity they’ve chosen to support. This may sound like a win-win: the fundraiser gets an exhilarating once-in-a-lifetime experience while raising money for a worthy cause. What could be the harm in that?

Quite a bit, actually. A study of two popular parachuting centres found that, over a five-year period (1991 to 1995), approximately 1,500 people went skydiving for charity and collectively raised more than £120,000. That seems pretty impressive until you consider a few caveats.

First, the cost of the diving expeditions came out of the donations, so of the £120,000 raised, only £45,000 went to charity.

What’s more, because most of the skydivers were first-time jumpers, they suffered a combined total of 163 injuries, resulting in an average hospital stay of nine days.

In order to treat these injuries, the UK’s National Health Service spent around £610,000. That means that for every £1 raised for the charities, the health service spent roughly £13. Ironically, many of the charities supported focused on health-related matters.1

That said, in our research, we’ve found that any college graduate in a rich country can do a huge amount to improve lives. And they can do this without changing jobs, or making big sacrifices.

We’ll cover three examples: donating 10% to an effective charity, advocating for important causes, and helping others be more effective.

1. Donating effectively

How can you take whichever job you find the most fun and personally rewarding, and do a huge amount of good?

Give 10% of your income to the world’s poorest people. It really is as simple as that.

How much good can donations do?

Since 2008, GiveDirectly has made it possible to give cash directly to to the poorest people in East Africa via mobile phone.

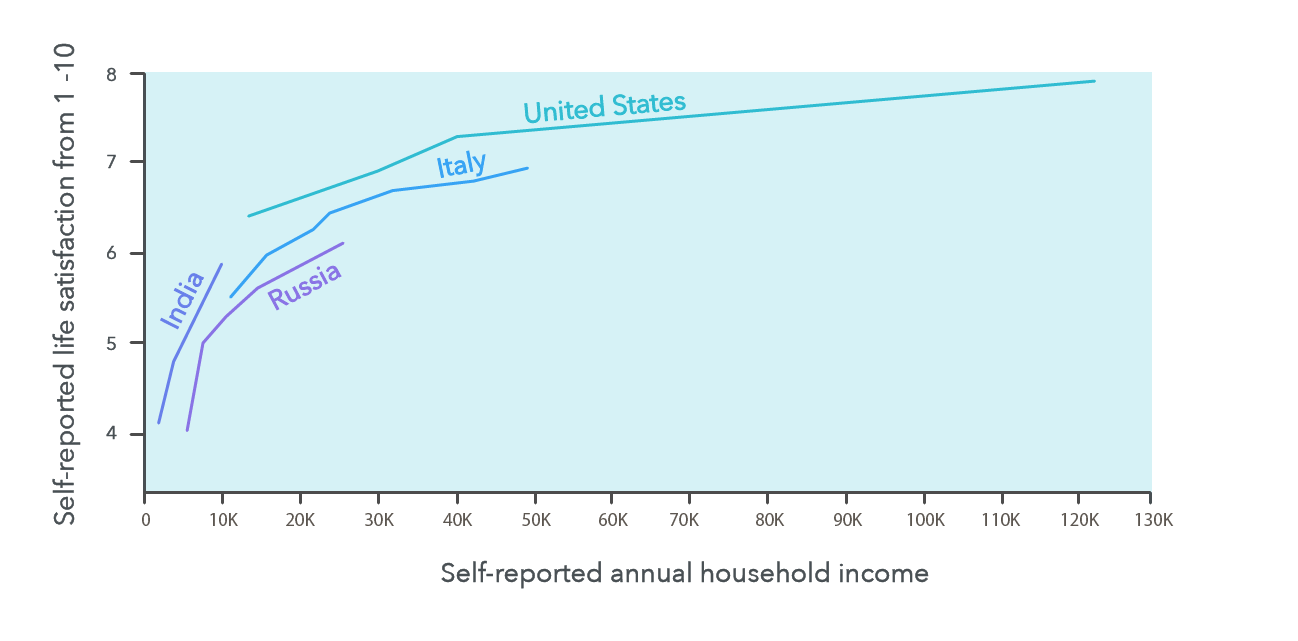

As we saw in part one, the more money you have, the less additional money will improve your life. For instance, in the US, a doubling of income is only associated with about half a point gain in life satisfaction, on a scale of one to ten.

These surveys have been extended across the world. There are examples in the chart below. (See more detail on this research.)

If someone earning that average level of income were to donate 10%, she could double the annual income of 11 people living in extreme poverty each year. Over the course of her career, she could have a major positive impact on hundreds of people.

Grace, 48, is a typical recipient of donations from GiveDirectly. She’s a widow who lives with four children:

GiveDirectly conducted a randomised controlled trial of their programme, and found that recipients experienced significant reductions in hunger, stress and other bad outcomes for years after receiving the transfers. These results add to substantial existing literature showing that cash transfers have significant benefits.I would like to use part of the money to build a new house since my house is in a very bad condition. Secondly, I would wish to pay fees for my son to go to a technical institute….

My proudest achievement is that I have managed to educate my son in secondary school.

My biggest hardship in life is [that I] lack a proper source of income.

My current goals are to build and own a pit latrine and dig a borehole since getting water is a very big problem.

How much sacrifice will this involve?

Regardless of which career you choose, you can donate 10% of your income.

Normally when we think of doing good with our careers, we think of paths like becoming a teacher or charity worker, which often earn salaries as much as 50% lower than jobs in the private sector, and may not align with your skills or interests. In that sense, giving 10% is less of a sacrifice.

Moreover, as we saw in an earlier article, once you start earning more than about $40,000 a year as an individual, any extra income won’t affect your happiness that much, while acts that help others like giving to charity probably do make you happier.

To take just one example, one study found that in 122 of 136 countries, if respondents answered “yes” to the question “did you donate to charity last month?”, their life satisfaction was higher by an amount also associated with a doubling of income.5 In part, this is probably because happier people give more, but we expect some of the effect runs the other way too.

(Not persuaded? Read more on whether giving 10% is better or worse for your happiness than not donating at all.)

How to have a bigger impact than being a doctor

The reason donations can be so effective is that it’s possible to send your money to the neediest people in the world, through the most effective organisations. So, although many charities aren’t effective, the best are.

And while GiveDirectly is certainly an effective charity, there are others that, some experts argue, are even better. The leading independent charity evaluator, GiveWell, estimates that the Against Malaria Foundation can prevent a death for every $7,500 in donations it receives.6 In addition, this provides other benefits that come with the treatment of malaria – such as overall quality of life and increased income – and this causes further ripple effects over time.

Donating 10% to the Against Malaria Foundation, therefore, could save more than one life every year.

These kinds of proven, cost-effective health programmes offer such a good opportunity to do good that even the most prominent aid sceptics have offered few arguments against them.

One life saved per year would amount to 40 lives saved over a 40-year career. In the previous article, we estimated that a typical doctor in clinical medicine saves five lives over their career. So by donating 10%, you could achieve 8 times as much impact.

And, we’ve just used Against Malaria Foundation and GiveDirectly to provide a concrete lower-bound on what you can achieve. We actually think there are many charities that are even more effective, working on higher-leverage approaches, such as research and advocacy, or on less conventional areas, such as pandemics. We write more about these areas later in the guide, and you can read more about which charities are highest-impact in a separate article.

If everyone in the richest 10% of the world’s population donated 10% of their income, that would be $3.5 trillion per year.7 Just 4% of that would be enough to raise everyone in the world above the $1.90/day poverty line. We could then provide universal education, double scientific research spending, fund a new renaissance in the arts…and still have much more left over.8

How is this possible?

It’s astonishing that we can do so much good while sacrificing so little. Why is this possible?

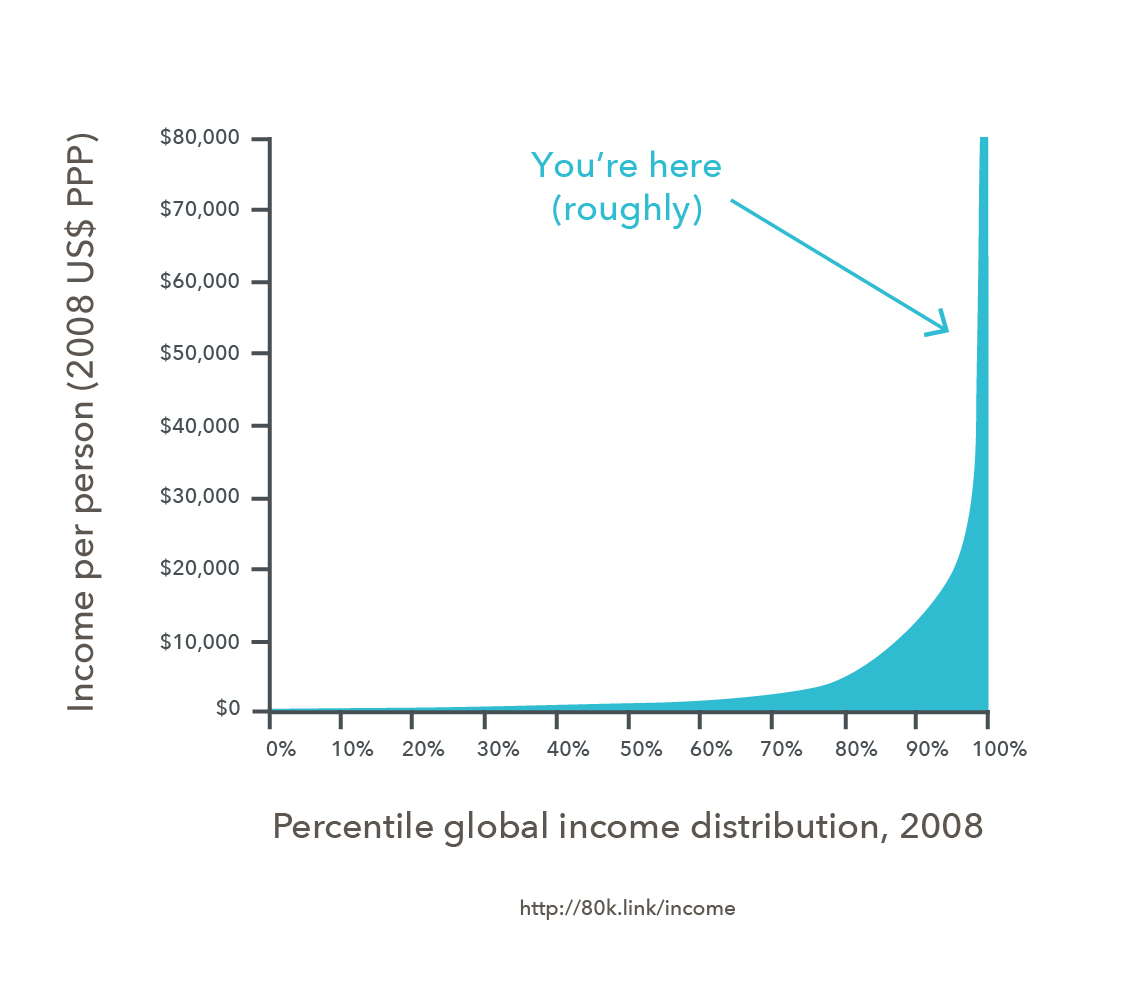

Consider one of the most important graphs in economics, the graph of world income:

The x-axis shows the percentage of people in the world who earn each level of income (as indicated by the y-axis). Income has been adjusted to indicate how much that specific dollar amount will buy in a person’s home country (i.e. purchasing power parity). If the world were completely equal, the line would be horizontal.

As Westerners, we know we’re rich, but we don’t think of ourselves as the richest people in the world – we’re not the bankers, CEOs or celebrities, after all. But actually, if you earn $54,000 per year after taxes and don’t have kids, then globally speaking, you are the 1%.

Find out how rich you are by using the quick calculator at the bottom of this page (which uses the same data we use in the chart, adjusted for inflation up to 2013).

These numbers are approximate, but it’s still the case that if you’re reading this, you are very likely in that big spike on the right of the graph (and perhaps even way off the chart), while almost everyone else in the world is in the flat bit at the bottom that you can hardly even see.

There’s no reason to be embarrassed by this fact, but it does emphasise how important it is to consider how you can use your good fortune to help others. In a more equal and intuitive world, we could just focus on helping those around us, and making our own lives go well. But it turns out we have an enormous opportunity to help other people with little cost to ourselves – and it would be a terrible shame to squander it.

Take action right now

All of us at 80,000 Hours were so persuaded by these arguments that we pledged to give at least 10% of our lifetime income to the world’s most effective charities. We did it through an organisation called Giving What We Can, with whom we are partnered. Our co-founder, Will, actually went a bit further and pledged to donate any income he earns above $35,000 a year to charity.

Giving What We Can enables you to take a public pledge to give 10% of your income to the charities you believe are most effective. They also provide research-backed recommendations on where to give.

You can take the pledge in just a few minutes. It’s likely to be the most significant thing you can do right now to do more good with your life.

It’s not legally binding, you can choose where the money goes, and if you’re a student, it only commits you to give 1%. You’ll be joining over 2,500 people who’ve collectively pledged over a billion dollars.

And if you’re not quite ready yet, Giving What We Can allows you to pledge 2% for one year to see how it goes before making any long-term commitment: try out giving. If you’d like to learn more about how to pick an effective charity, read our article.

2. What if you don’t want to give money? How to help through effective advocacy

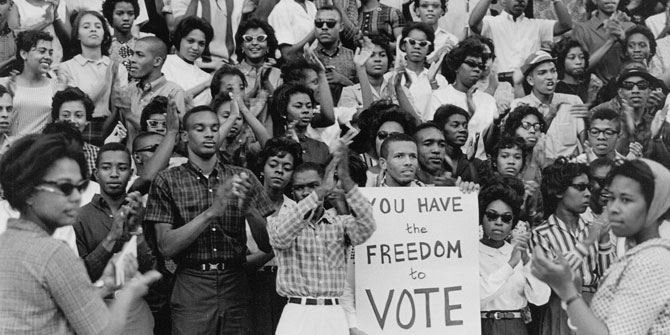

Rich countries have a disproportionate impact on issues like global trade, migration, climate change and technology policy, and are at least partly democratic. So if you’d prefer to do something besides giving money, consider advocating for important issues.

We were initially sceptical that one person could have real influence through political advocacy, but when we dug into the numbers, we changed our minds.

Let’s take perhaps the simplest example: voting in elections. Several studies have used statistical models to estimate the chances of a single vote determining the US presidential election. Because the American electoral system is determined at the state, not individual, level, if you live in a state that strongly favours one candidate, your chance of deciding the outcome is effectively zero. But if you live in a state that’s contested, your chances rise to between one in ten million and one in a million. That’s quite a bit higher than your chances of winning the lottery.

And remember, the US Federal Government is big. Really big. Let’s imagine one candidate wanted to spend 0.2% more of GDP on foreign aid. That would be about $144 billion extra foreign aid over their four year term.10 One millionth of that is $144,000 dollars. So voting could be the most important hour you’ll spend that year. (The figures are similar in other rich countries – smaller countries have less at stake, but each vote counts for more. Read more about these estimates.)

The key with political advocacy is that, although your influence is extremely small, the stakes are extremely high. So a single vote, letter to your Congressperson, or question at a town hall can have a big impact. This is even more true if you’re careful to focus on the most important issues, which we cover in the next article.

3. Do good by helping others be more effective

Suppose you don’t have any money or influence. What then? One option is to go and get some. We cover how to invest in yourself, no matter what job you have, in a later article.

That aside, you probably know someone who does have some influence. So you can make a difference by helping them be more effective.

For instance, if you could enable one other person to give 10% of their income to charity, that would have as much impact as doing it yourself. The same is true for mobilising support for other important causes, such as persuading people to give up factory-farmed meat, or vote in an election. Many of our readers have persuaded others of things like this by leading by example.

We know someone who set up 1% payroll giving at their company, and in the process, raised far more money for charity than they could have given themselves. We know lots of people who have raised hundreds of dollars for effective charities by donating their birthday presents.

Volunteering can be effective, so long as you’re volunteering for effective organisations, and doing so in a way that uses your skills, or will help you learn to be more effective in the future.

Or consider Kyle, who became the assistant to a researcher he thinks is doing world-changing work. If he can save that researcher time compared to the next best assistant, then he’s enabling the scientist to perform more research, and also contributing to the world-changing work.

We’re reminded of an old (most likely fictional) story about a time when President John F. Kennedy visited NASA. Upon meeting a janitor, Kennedy asked him what he was doing. The janitor replied, “Well, Mr. President, I’m helping put a man on the moon”.

Conclusion: how anyone can make a difference

So, good news: you don’t need to throw yourself out of a plane to do good. In fact, there are far easier (and safer) ways to have an impact that are much more effective.

Due to our fortunate positions in the world, there’s a lot we can do to make a difference without making significant sacrifices, whatever jobs we end up in. We’ve covered three examples:

- Giving 10% to the world’s poorest people, or other effective charities.

- Using your political influence, such as by voting.

- Aiding others in having an impact.

Or take a moment to consider how else you might be able to make a big impact with little sacrifice. There are many more options.

What if you want to make a difference directly through your career? If you can achieve so much with such little sacrifice, then what you could achieve with your entire job could be huge. That’s what we’ll cover in the next three articles.

Part 4:How to choose where to focus

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide.

No time right now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week.